Where do we observe accreting neutron stars?

Accreting neutron stars are commonly found in X-ray pulsars and pulsating ultraluminous X-ray sources , where they accrete matter from a companion star in a binary system. The strong magnetic field of the neutron star confines the inflowing plasma and channels it onto the magnetic poles, converting gravitational energy into X-ray emission. Because the magnetic axis is typically misaligned with the spin axis, the rotating neutron star produces X-ray pulsations, as demonstrated in the video below (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech).

What is my research on neutron star accretion?

At sufficiently high accretion rates, a radiative shock forms above the stellar surface. Below the shock, the magnetically confined inflow slowly sinks, forming a column-like structure near the magnetic poles. Within this accretion column, mechanical energy is converted into radiation: lateral diffusion produces sideways emission that cools the system, while radiation pressure provides vertical support, maintaining the column against gravity.

To study this system, we perform a series of numerical simulations that solve the relativistic magnetohydrodynamic equations coupled with radiation transfer, investigating the dynamical behavior of the accretion column under varying accretion rates, magnetic field strengths, and flow geometries. In a major advancement, our latest models are first to include a fully integrated opacity scheme that captures essential microphysics — magnetic electron scattering, magnetic bremsstrahlung, cyclotron resonance, vacuum polarization, and electron-positron pair production.

What do we learn from this study?

- Accretion columns are highly dynamical and exhibit high-frequency (kHz) nonlinear oscillations. Our work provides the first clear theoretical explanation for these oscillations, resolving a decades-old puzzle in neutron star astrophysics. We show that the oscillations arise not from photon bubbles, as long speculated, but from a fundamental imbalance between heating via vertical radiation advection and cooling through lateral diffusion. These oscillations are essential: they regulate how the shock-released accretion power is redistributed, enabling the column to maintain vertical support against gravity and achieve thermal balance. Although photon bubbles are not the driving mechanism, they naturally emerge within the radiation-dominated column and enhance vertical radiation transport, amplifying the resulting luminosity variations. This discovery not only clarifies the physical origin of kHz oscillations in accretion columns from first principles, but also offers a concrete prediction to guide future observational searches.

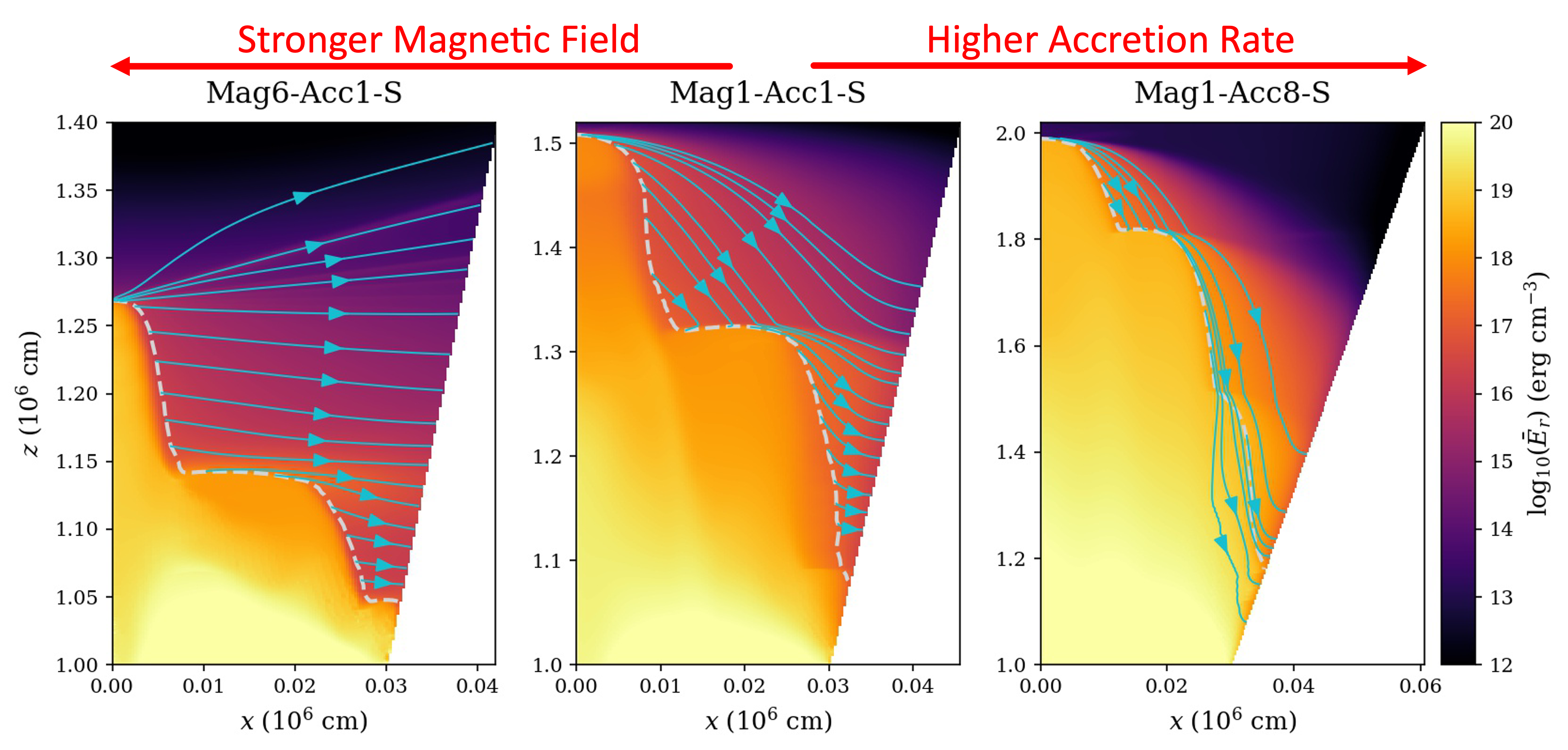

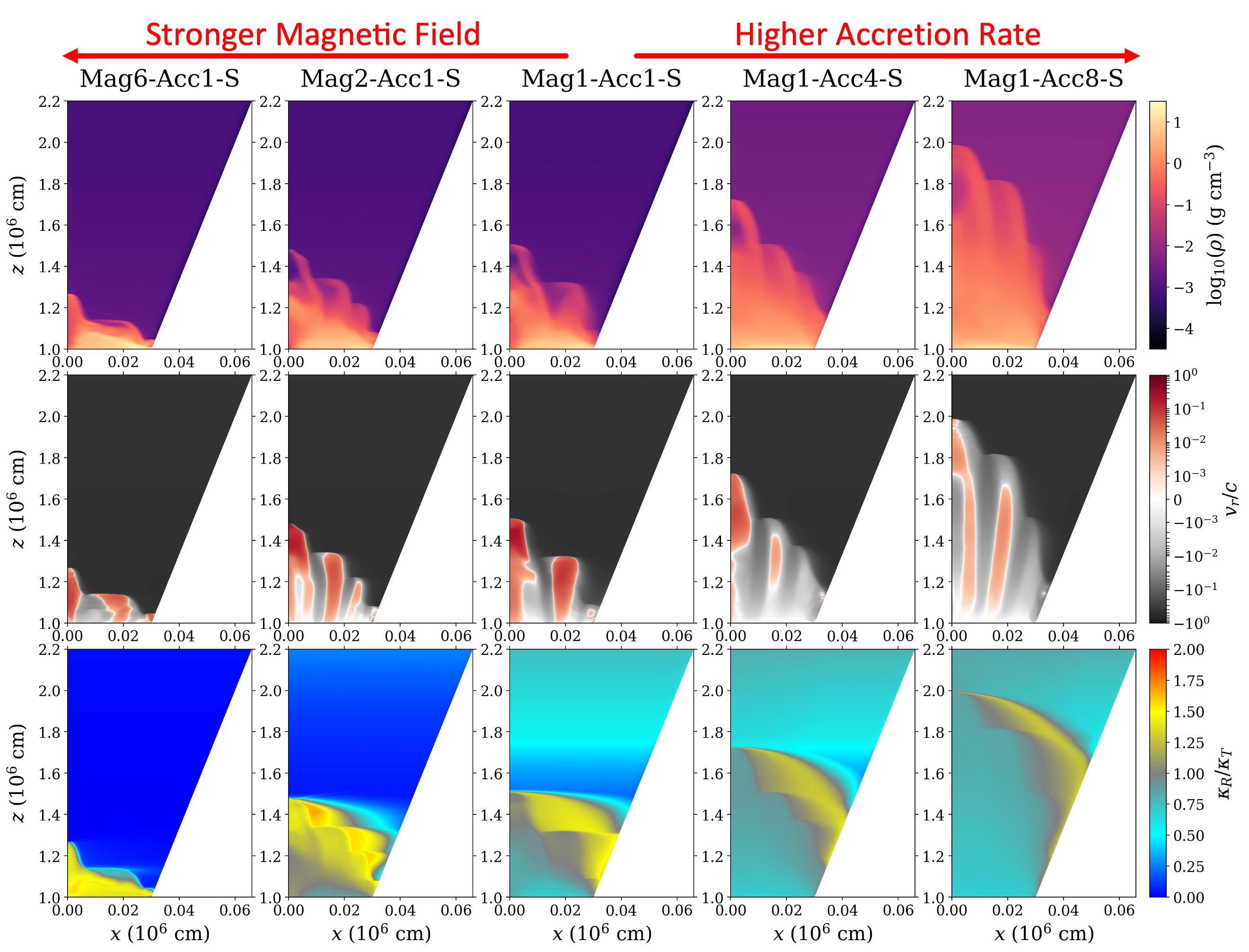

- For the first time, we show that downward radiation scattering above the shock plays a crucial role in shaping sideways emission and influencing the height of the accretion column. When this scattering is strong, it re-injects heat back into the column, increasing its height, while also compressing sideways emergent radiation, which can smear out shock oscillation signature. The strength of this effect depends on both the local magnetic field and the accretion rate: stronger magnetic fields and lower accretion rates reduce gas-photon interactions, thereby weakening the scattering. This finding helps narrow the physical window where high-frequency (kHz) signals are most likely to be observed. The accretion rate must be high enough to sustain a radiation-dominated column, and the magnetic field strong enough to laterally confine the flow and maintain the column structure. However, if the accretion rate is too high or the magnetic field too weak, downward scattering dominates and suppresses the emergent oscillation signal.

- Our parameter survey reveals a clear connection between shock oscillation frequency and column geometry: taller and wider columns oscillate more slowly because of their longer thermal response times. We show that column height — and thus the oscillation frequency — is primarily set by the magnetic field strength and accretion rate. At fixed accretion rate, stronger magnetic fields suppress downward scattering, resulting in shorter columns. At fixed magnetic field strength, higher accretion rates lead to taller columns due to increased energy input. Further details are available in our listed publications.

Publications

-

A Parameter Survey of Neutron Star Accretion Column Simulations

Zhang, L., Blaes, O., Jiang, Y.-F.

2025, MNRAS, 540, 3934 -

Radiative relativistic magnetohydrodynamic simulations of neutron star column accretion

Zhang, L.

2023, PhD thesis, UC Santa Barbara -

Dynamical Effects of Magnetic Opacity in Neutron Star Accretion Columns

Sheng X., Zhang, L., Blaes, O., Jiang, Y.-F.

2023, MNRAS, 524, 2431 -

Dynamics of Neutron Star Accretion Columns in Split-Monopole Magnetic Fields

Zhang, L., Blaes, O., Jiang, Y.-F.

2023, MNRAS, 520, 1421 -

Radiative Relativistic Magnetohydrodynamic Simulations of Neutron Star Column Accretion in Cartesian Geometry

Zhang, L., Blaes, O., Jiang, Y.-F.

2022, MNRAS, 515, 4371 -

Radiative MHD Simulations of Photon Bubbles in Radiation-Supported Magnetized Atmospheres of Neutron Stars with Isotropic Thomson Scattering

Zhang, L., Blaes, O., Jiang, Y.-F.

2021, MNRAS, 508, 617