Why do we study black hole accretion?

Black holes can power some of the brightest phenomena in the universe, emitting light across the entire electromagnetic spectrum - from radio and millimeter wavelengths to infrared, optical, ultraviolet, X-ray, and even gamma-ray bands. Such luminous activity arises in systems like active galactic nuclei (AGN; including quasars), X-ray binaries, ultraluminous X-ray sources, and tidal disruption events. In many of these sources, the radiation output approaches or even exceeds the Eddington limit, where radiation pressure becomes strong enough to shape the structure and motion of the surrounding gas. Studying these extraordinary systems allows us to uncover the underlying physical mechanisms — such as how jets and winds are launched and how they shape the radiation we observe. These studies also connect to broader cosmic questions, including how black holes grow from stellar to supermassive scales and how radiation-driven feedback influences the formation and evolution of galaxies.

What is my research on black hole accretion?

My research uses large-scale numerical simulations to explore how matter falls onto black holes and releases energy. These simulations solve the fundamental conservation laws that govern accretion, allowing us to bridge first-principles theory with astronomical observations. In extremely luminous systems, intense radiation can drive powerful outflows that obscure the inner regions and scatter much of the emitted light. The resulting emission depends strongly on viewing angle, making it challenging to determine whether observed features reflect intrinsic flow properties or merely orientation effects. Therefore, numerical experiments are essential for resolving this complexity: by self-consistently capturing the nonlinear interaction among radiation, matter, and magnetic fields, they connect the physical conditions around black holes to the signals we detect, revealing the physics hidden behind the light.

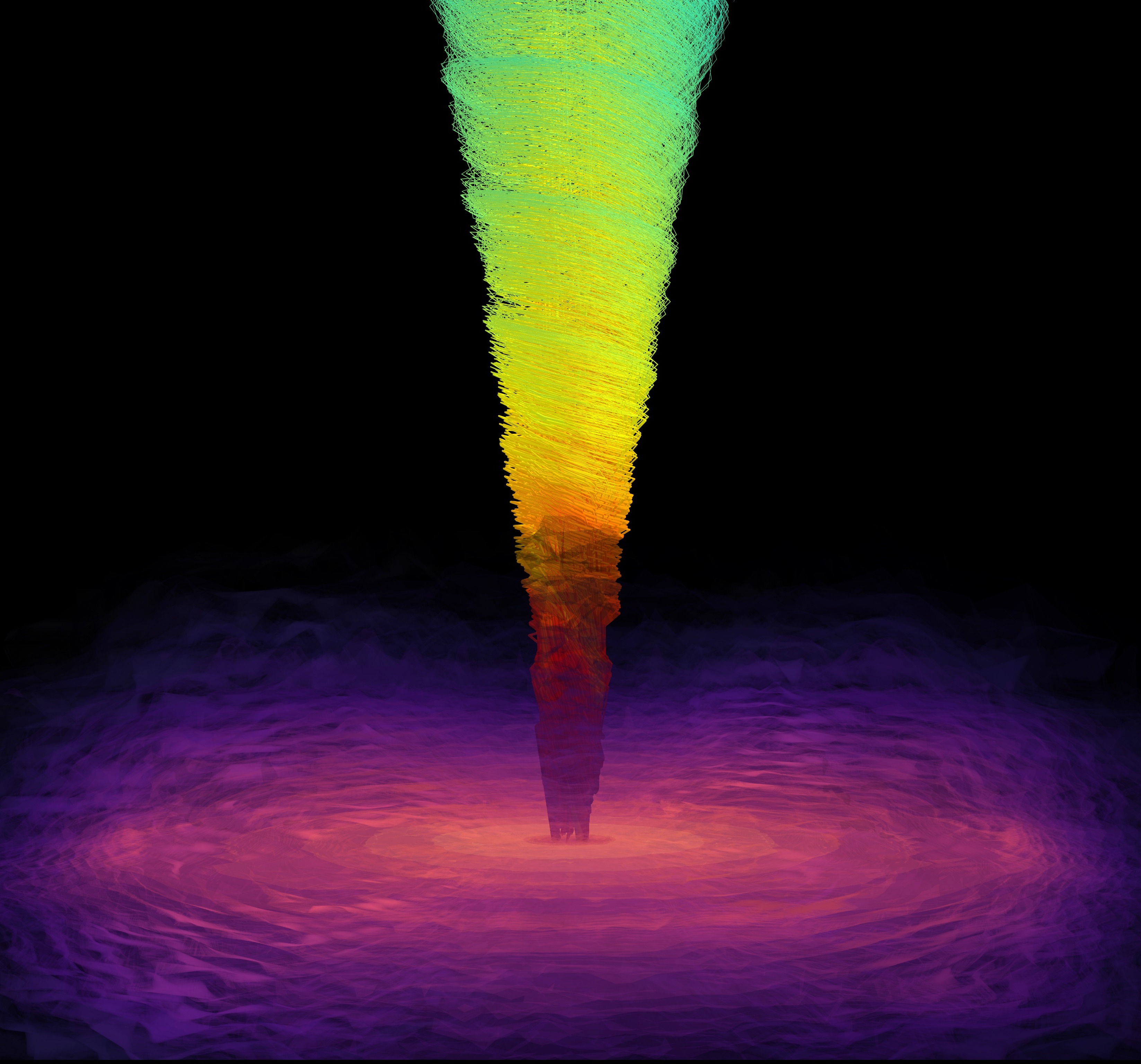

In particular, we conduct a parameter survey of stellar-mass black hole accretion simulations, covering a broad range of accretion rates as well as two black hole spins and magnetic field topologies. To capture how radiation and magnetic fields shape the accretion flow, we solve the equations of general relativistic magnetohydrodynamics (GRMHD) coupled with angle-dependent radiation transfer. The video below shows the evolution of a black hole accreting at a super-Eddington rate, accompanied by the formation of a relativistic jet.

An interesting property of black hole accretion is its scale-free nature: as long as the gas remains fully ionized and Thomson scattering dominates, the underlying dynamics are independent of black hole mass. Therefore, our stellar-mass black hole simulations can be directly applied to the inner regions of AGN disks and serve as a foundation for future extensions of our numerical studies to supermassive black holes.

What do we learn from this study?

-

Partition of Radiation-Dominated Black Hole Accretion Systems:

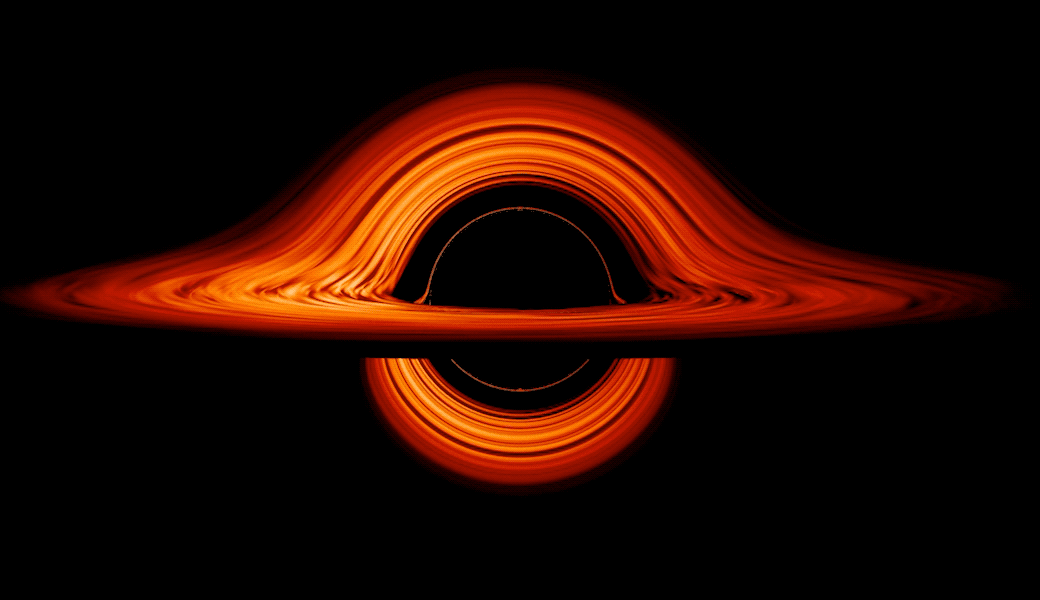

In radiation-dominated systems, accretion onto black holes converts gravitational energy into vast numbers of energetic photons. These photons exert intense radiation pressure, feeding back on the accretion flow and driving powerful winds. Near a spinning black hole, the frame-dragging of curved spacetime twists the magnetic field lines and helps launch relativistic jets, particularly when a strong poloidal magnetic field is present. As illustrated in Figure 1, such an accretion system can be broadly divided into three regions:

a. Disk region - where the accretion process occurs as gas remains gravitationally bound and flows inward.

b. Wind region - where gas becomes unbound and is pushed outward primarily by radiation forces.

c. Jet region - where gas is accelerated to relativistic speeds by magnetic fields twisted near the black hole’s poles.

-

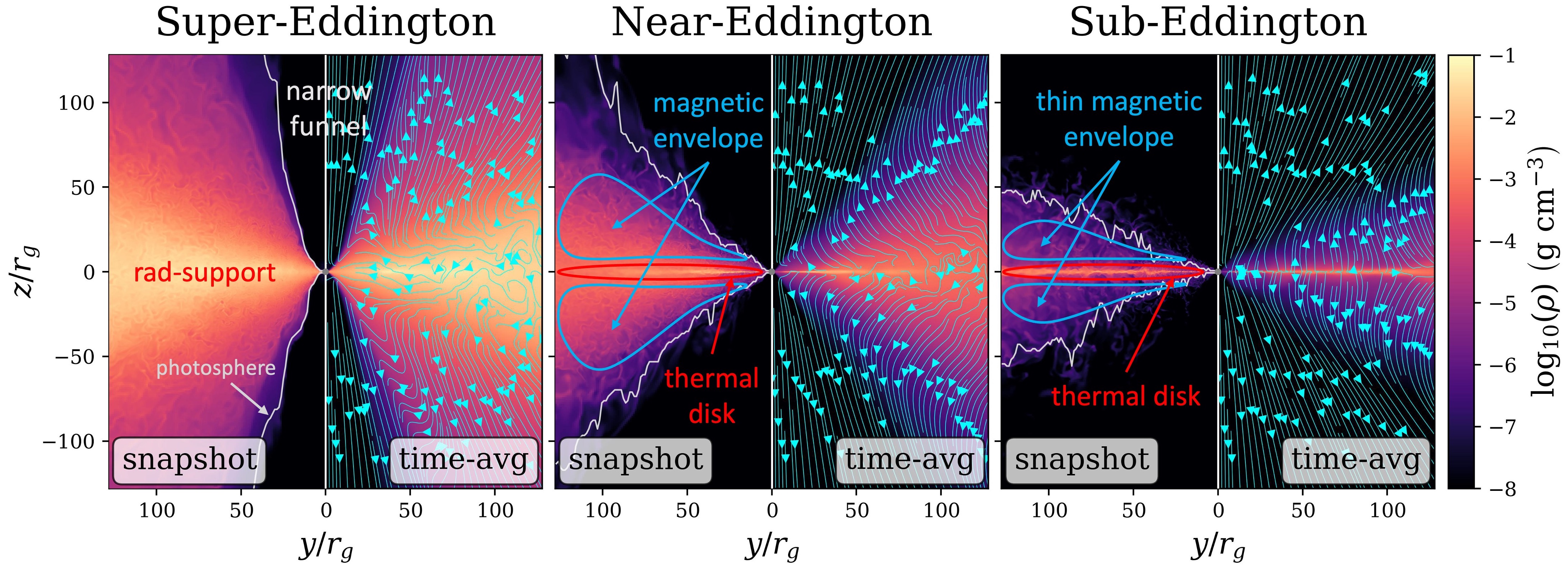

Flow Structures Across Accretion Regimes:

This parameter survey significantly advances our understanding of radiation-dominated accretion flows by systematically exploring a wide range of accretion rates. Figure 2 presents three representative models illustrating the distinct regimes revealed by these simulations. In the super-Eddington regime, the accretion flow forms a geometrically thick, radiation-supported disk accompanied by powerful outflows. Radiation becomes largely trapped and advected inward, producing a narrow, funnel-shaped photosphere. As the accretion rate decreases to the near-Eddington regime, the funnel opens, allowing radiation to escape more efficiently through diffusion. The disk develops a dense, thin midplane layer surrounded by a magnetically dominated envelope, which stabilizes the flow and suppress thermal instability. In the sub-Eddington regime, the magnetic envelope becomes both geometrically and optically thinner, exposing the midplane more directly and producing radiation that is more thermal in nature. Together, these models provide a coherent picture of how the structure of accretion flows varies with accretion rate and luminosity. They also show broad agreement with observations and offer predictive diagnostics for future studies. Further details are provided in our listed publications.

-

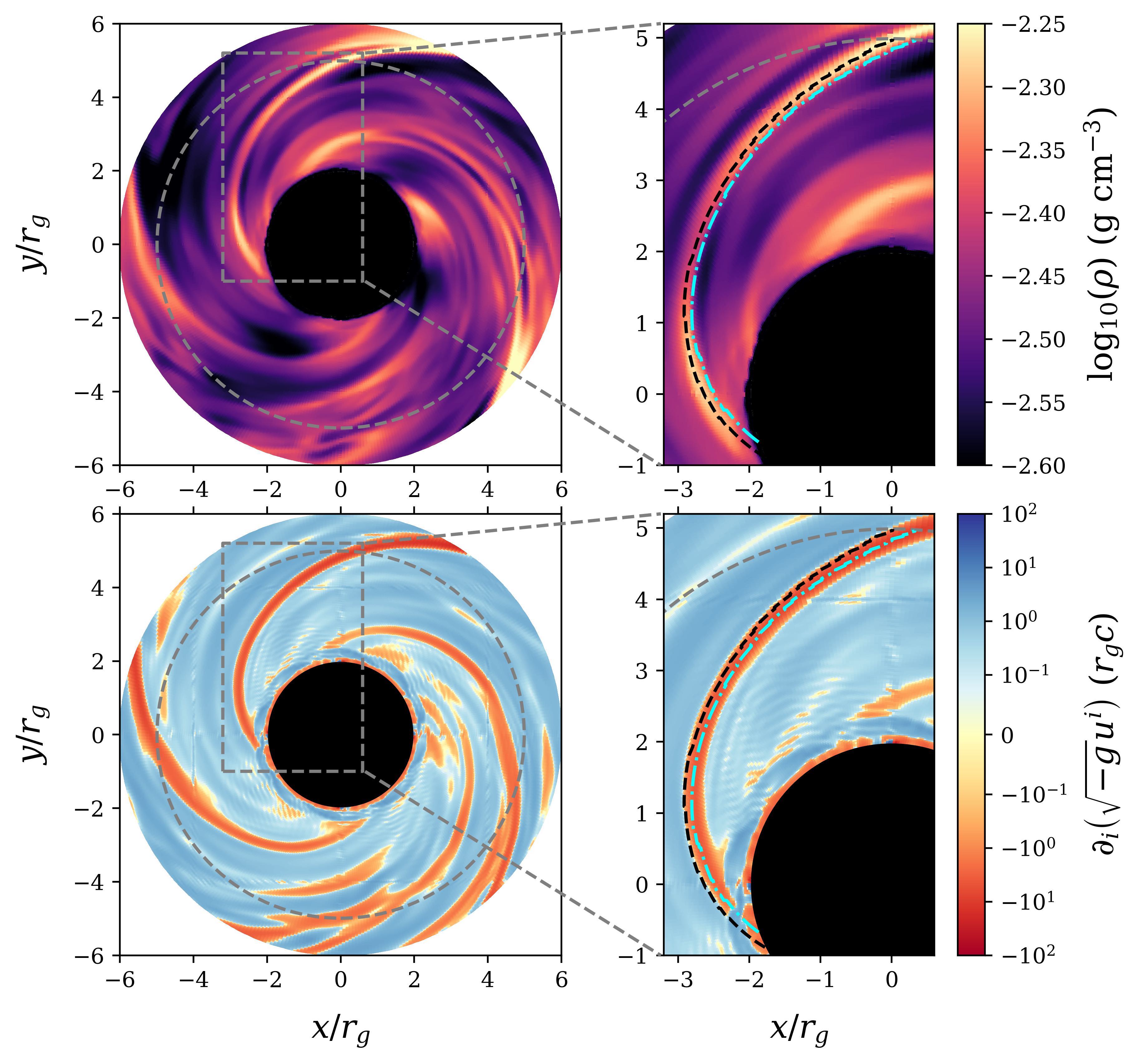

Relativistic Jets and the Plunging Region:

Incorporating general relativity into the simulations naturally captures both jet formation and the dynamics of the plunging region. With sufficient net vertical magnetic flux, a rapidly spinning black hole can generate powerful relativistic jets that evacuate the funnel region, as shown in Figure 3a. In contrast, when the poloidal magnetic field is weak, only a weak jet forms and fails to clear the funnel, which then fills with radiation-driven outflows and produces distinct observational signatures. Within the plunging region, the fluid properties vary smoothly, showing no sharp transition across the inner edge of the disk. Angular momentum transport in this region is dominated by Maxwell stress rather than fluid Reynolds stress. As shown in Figure 3b, spiral structures develop and extend throughout the plunging region. The density maxima along each spiral are shifted by roughly 90 degrees from the locations of zero velocity divergence, indicating that these wave patterns arise primarily from compression, analogous to density waves.

Publications

-

Radiation GRMHD Models of Accretion onto Stellar-Mass Black Holes: IV. Sub-Eddington Accretion

Zhang, L., Stone, J.M., Davis, S.W., Jiang, Y.-F., Mullen, P.D., White, C.J.

2026, in preparation -

Radiation GRMHD Models of Accretion onto Stellar-Mass Black Holes: III. Near-Eddington Accretion

Zhang, L., Stone, J.M., Davis, S.W., Jiang, Y.-F., Mullen, P.D., White, C.J.

2025, in preparation -

Radiation GRMHD Models of Accretion onto Stellar-Mass Black Holes: II. Super-Eddington Accretion

Zhang, L., Stone, J.M., White, C.J., Davis, S.W., Jiang, Y.-F., Mullen, P.D.

2025, submitted to ApJ -

Radiation GRMHD Models of Accretion onto Stellar-Mass Black Holes: I. Survey of Eddington Ratios

Zhang, L., Stone, J.M., Mullen, P.D., Davis, S.W., Jiang, Y.-F., White, C.J.

2025, accepted by ApJ -

Magnetosonic Waves as a Potential Driver of Observed Temperature Fluctuation Patterns in AGN Accretion Disks

Kaul, I., Blaes, O., Jiang, Y.-F., Zhang, L.

2025, ApJ, 991, 194 -

The Plunging Region of a Thin Accretion Disc around a Schwarzschild Black Hole

Rule, J., Mummery, A., Balbus, S., Stone, J., Zhang, L.

2025, MNRAS, 542, 377 -

Radiation and Magnetic Pressure Support in Accretion Disks Around Supermassive Black Holes and the Physical Origin of the Extreme-ultraviolet to Soft X-ray Spectrum

Jiang, Y.-F., Blaes, O., Kaul, I., Zhang, L.

2025, ApJ, 988, 43